Atlantic Sturgeon

Acipenser oxyrhynchus

Fish Illustrations by: Roz Davis Designs, Damariscotta, ME (207) 563-2286

With permission, the use of these pictures must state the following: Drawings provided courtesy of the Maine Department of Marine Resources Recreational Fisheries program and the Maine Outdoor Heritage Fund.

Common name: Atlantic Sturgeon, sea sturgeon

Scientific name: Acipenser oxyrhynchus

Range: The historical and current range of Atlantic sturgeon includes major estuaries and river systems from Canada to Florida. While still found throughout their historical range, Atlantic sturgeon have been locally extirpated in certain areas and spawning is known to occur in only 22 of 38 historical spawning rivers. Adult and subadult Atlantic sturgeon also range widely throughout the marine environment. While in the ocean, they tend to stay in the shallow waters of the continental shelf, down to a depth of around 250 feet.

The coastwide Atlantic sturgeon population is made up of five distinct population segments (DPSs): (1) Gulf of Maine (GOM), (2) New York Bight, (3) Chesapeake Bay, (4) Carolina, and (5) South Atlantic.

In Maine, the best places to see sturgeon are in the Androscoggin, Kennebec, and Penobscot rivers. The Kennebec River has the biggest spawning aggregation. In 2023, Maine Public covered a story that estimated there were at least 200 sturgeon just upstream from where Cobbossee stream flows into the Kennebec River in Gardiner. The Abanaki word “cobbossee” can be translated as “the place where the sturgeon are”, and there are often hundreds or thousands of sturgeon to be seen there.

Identification: Atlantic sturgeon are primitive looking fish, probably best known for the caviar (fish eggs) they produce. They have a long fossil record, dating back 120 million years, and their ancestors, which looked very similar to their modern form, roamed the earth with dinosaurs 245 million years ago.

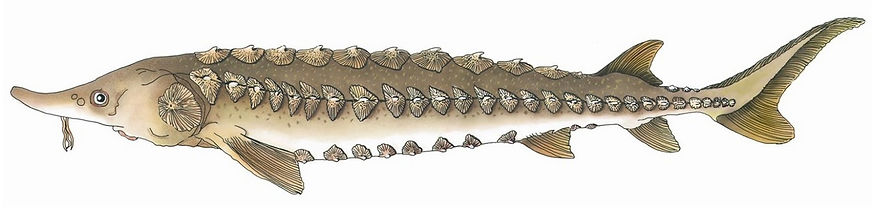

Atlantic sturgeon are olive green or blue gray above, gradually fading on the sides to a white underbelly. They have five rows of bony plates known as scutes that run along their body and a snout with four whisker-like projections called barbels that hang down in front of their mouth. Their tail fin resembles the tail fin of some sharks in that the upper lobe measures much longer than the lower lobe.

They are one of only two species of sturgeon found in Maine; the other being shortnose sturgeon. While the two species are overall similar in appearance, Atlantic sturgeon are much larger, growing up to 14-16 feet in length and weighing up to 800 pounds. Additionally, they also have a proportionally smaller mouth, different snout shape, and tail scute pattern.

Life history: Atlantic sturgeon are anadromous fish that hatch in freshwater rivers, head out to sea as sub-adults, and return to their birthplace to spawn when they reach adulthood. Atlantic sturgeon spawning intervals range from 1 to 5 years for males and 2 to 5 years for females, with males returning almost every year and females usually returning every other year or every third year. In the south (rivers from Georgia to the Chesapeake Bay), scientists have confirmed that adult sturgeon spawn during the late summer and fall. In the north (rivers from Delaware to Canada), adults spawn in the spring and early summer. After spawning, males in northern rivers may remain in the river or lower estuary until the fall, while females typically exit the rivers within 4 to 6 weeks after spawning.

Atlantic sturgeon spawn in flowing waters with solid substrates, at water temperatures ranging from 56-67 ºF. Female egg production correlates with age and body size, and ranges from 400,000 to 2 million eggs. Once laid, the eggs stick to the substrate until they hatch. Upon hatching, larvae hide along the bottom and drift downstream until they reach brackish waters where they may reside for 1 to 5 years before moving into nearshore coastal waters. Tagging data indicate that these immature Atlantic sturgeon travel widely up and down the East Coast and as far as Iceland once they leave their natal rivers. Most of their growth is believed to occur out at sea where they feed on various invertebrates and small fish.

Atlantic sturgeon are long lived and slow-to-mature and their lifespan is correlated with how far north or south they live. They can live up to 60 years in Canada but likely only 25 to 30 years in the Southeast. Southern populations typically grow faster and reach sexual maturity earlier than northern populations. For example, Atlantic sturgeon mature in South Carolina rivers at 5 to 19 years of age, in the Hudson River at 11 to 21 years, and in the Saint Lawrence River at 22 to 34 years.

Diet and behavior: Atlantic sturgeon are gentle giants. Despite their gargantuan size, they are designed to be effective bottom feeders. Their fleshy barbels help to sense food in the mud. Their toothless mouth, which is located beneath their long snout, is capable of being thrust outward, allowing them to suck food off the bottom like a vacuum cleaner. They typically consume invertebrates, such as crustaceans, worms, and mollusks, and bottom-dwelling fish like sand lance.

Sturgeon are well known for their habit of leaping completely out of the water on their way upriver to spawn. However, scientists are still trying to understand why. There are several theories, such as communication, or to dislodge itchy sea lice. The theory currently gaining the most traction is that they jump to fill their swim bladders with air, which helps control where they can go in the water column. Research has found that they will change their location in the water column after jumping, and jump more frequently during tidal changes, which supports the swim bladder theory. The best time to see sturgeon jumping is between May and August, especially when the tide is changing. In Maine, good viewing spots can be found along the lower Androscoggin and Kennebec Rivers, such as below the Brunswick dam or just downriver from the site of the former Edwards dam.

Cultural importance: Humans have a longstanding relationship with sturgeon. Indigenous tribes have harvested Atlantic and shortnose sturgeon for their meat and eggs (roe) beginning some 4,000 years ago. The Wabanaki, who have stewarded the land and resources of northeastern New England for thousands of years, harvested sturgeon and had a spiritual connection to the fish. The name of the Passagassawakeag River is Native in origin and is believed to mean, “a place for spearing sturgeon by torchlight.”

Sturgeon are credited as the primary food source that saved the Jamestown settlers in 1607. Atlantic sturgeon were once found in great abundance, but their populations have declined greatly due to overfishing and habitat loss. Atlantic sturgeon were prized for their eggs, which were valued as high-quality caviar. Unfortunately for the sturgeon, the traditional way to harvest caviar involves cutting the adult females open to remove the eggs, killing them in the process. During the late 1800s, people flocked to the eastern United States in search of caviar riches from the sturgeon fishery, known as the “Black Gold Rush.” Thanks to this spike in mortality from caviar harvest, by the beginning of the 1900s sturgeon populations had declined drastically.

Threats: The major causes of historic population decline for sturgeon were overfishing and the loss of habitat from dams. While overfishing is no longer a threat due to protections from the Endangered Species Act, habitat loss is still a problem. Alongside dams, which block access to spawning areas and reduce reproductive success, the primary threats currently facing Atlantic sturgeon are unintended catch (bycatch) in some commercial fisheries, habitat degradation, and strikes from boats or by the blades of boats’ propellers.

Atlantic sturgeon need hard bottom substrates in freshwater reaches for successful spawning. This habitat can be disrupted, degraded, or lost because of various human activities, such as dredging, damming, and withdrawing water. These activities can also negatively affect water quality, which impacts development of sturgeon offspring. Sturgeon depend on clean, oxygen rich water, and can be an indicator of good water quality…or lack thereof. Due to their long life spans and late age of maturity, populations will likely be slow to recover. Additionally, there is still much we don’t know about sturgeon, so continued research is needed.

The 2024 stock assessment update concluded that Atlantic sturgeon remain depleted coastwide. The phrase “depleted” instead of “overfished” was due to the many factors that have contributed to the continued low abundance of Atlantic sturgeon, not just directed historical fishing. While overall levels of Atlantic sturgeon remain low, the population has shown signs of improvement.

Restoration efforts: Today, all five U.S. Atlantic sturgeon distinct population segments are listed as endangered or threatened under the Endangered Species Act. The Gulf of Maine distinct population segment (DPS) is the only one listed as threatened, with the remainder of the population segments listed as endangered. The species is also listed under CITES Appendix II. This designation means that across its range, Atlantic sturgeon are not necessarily at immediate risk of extinction but could become so if fishing is not regulated. For example, populations in Canada are not protected species under the U.S. Endangered Species Act, and have their own set of regulations.

NOAA Fisheries has developed a recovery outline to commence the recovery planning process for Atlantic sturgeon. The outline is meant to serve as an interim guidance document to direct recovery efforts until a full recovery plan is approved. Part of this recovery planning is to identify critical habitat areas. In Maine, the Androscoggin, Kennebec, and Penobscot rivers are all designated as critical habitat for Atlantic sturgeon.

Removal of outdated dams or providing ways for fish to get around those dams can greatly improve Atlantic sturgeon access to historical habitats. In the last two decades, Atlantic sturgeon have regained access to historic habitat following a handful of major dam removals. In Maine, the removal of the Edwards Dam on the Kennebec River in 1999 and the Veazie Dam on the Penobscot river in 2013, reconnected their historic range for the first time in a century. In time, access to these and other spawning grounds may help the fish to recover. The improvement of water quality in Maine’s rivers has also been very important to their recovery, thanks in large part to passage of the Clean Water Act of 1972, championed by Maine senator Ed Muskie.

Some Atlantic sturgeon are bred and held at research facilities, in accordance with specific permits. These animals can provide important insight into the physical, chemical, and biological parameters necessary for the optimal growth, survival, and reproduction of Atlantic sturgeon in the wild. One of the best ways to help save this amazing species is through outreach, and so some of these captive-bred animals may also be used to promote public awareness of the plight of the species.

Anyone can get involved in learning about and helping to restore sturgeon. The Students Collaborating to Undertake Tracking Efforts for Sturgeon (SCUTES) program provides lesson plans, educational kits, and an opportunity for classrooms to adopt a tagged sturgeon. If you find a dead, entangled, or stranded sturgeon, report it to NOAA by sending an email to noaa.sturg911@noaa.gov or by calling a local office. This allows scientists to collect samples and data to better understand sturgeon populations, track recovery efforts, identify threats, and fill in gaps in our knowledge. For more information, click here: https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/new-england-mid-atlantic/endangered-species-conservation/report-stranded-injured-or-dead-sturgeon

Fishery: Indigenous peoples, including the Wabanaki, harvested sturgeon long before Europeans arrived in North America. Since colonial times, Atlantic sturgeon have supported commercial fisheries of varying magnitude. The earliest documented fishery in Maine was in 1628 at Pejepscot Falls on the Androscoggin River. In the mid-1800s, Atlantic and shortnose sturgeon began to support a thriving and profitable fishery for caviar, smoked meat, and oil, second only to lobster among important fisheries.

Historical records generally failed to differentiate between landings of Atlantic sturgeon and the smaller shortnose sturgeon, making it difficult to determine historical trends in abundance for populations of either species. However, the overall decline of sturgeon populations was swift and dramatic, starting with the “black gold rush” in the 1800s. Close to 7 million pounds of sturgeon were reportedly caught in 1887, but by 1905, the catch declined to only 20,000 pounds. Landings continued to decline through the 20th century, leading to the enactment of strict regulations. In 1983, Maine closed the tidal waters of the Kennebec and Androscoggin to the harvest of sturgeon, and instituted a 72-inch minimum size for other areas. In 1992, the harvest of sturgeon (both species) became illegal in Maine’s coastal waters. Both shortnose and Atlantic sturgeon are protected under the Endangered Species Act in 2012, and harvest is strictly prohibited.

Today, much of the world’s caviar is produced through farm raised fish. While the predominant method of harvesting the eggs still results in fish mortality, there is a newer and much less common “no kill” method that uses hormone therapy combined with milking techniques and/or C-section-like surgery to get eggs without harming the fish.

Sources:

https://www.maine.gov/dmr/fisheries/recreational/anglers-guide/do-you-know-your-catch

https://cites.org/eng/app/index.php

https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/species/atlantic-sturgeon

https://www.fws.gov/species/atlantic-sturgeon-acipenser-oxyrinchus-oxyrinchus

https://downeast.com/land-wildlife/maines-best-bars-for-watching-sturgeon/

https://www.embarkmainetours.com/tour-talk/monsters-of-the-kennebec

https://umaine.edu/marine/2017/10/16/atlantic-sturgeons-sojourn/